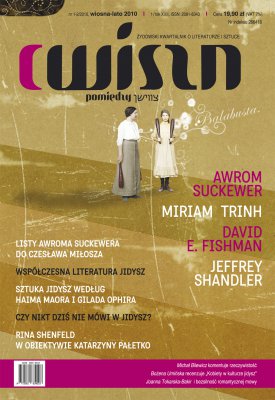

No 1-2/2010

Contemporary Yiddish Culture/ Yiddish in Contemporary Culture

What is inside?

The cover story of this very first issue of the Cvishn presents today’s Yiddish and Yiddish in an attempt to diagnose its both vernacular and postvernacular condition – as Jeffrey Shandler would say. Two couples, from Israel and Germany (Miriam Trinh and Eliezer Niborski, and Prof. Simon Neuberg, respectively) share their experiences as parents who try to raise their children speaking and using Yiddish at home in the context of missing Yiddish linguistic environment. They talk about challenges they face and their hopes that what they do and witness as parents – this “linguistic synthesis (of their children inventing cross-language words when they lack one), proving live ability of bilingual creation, contains one of the answers to the question: 'Who will remain? What will remain?’[1] ” asked by Avrom Sutzekever (see below) about 30 years ago.

Their discussion is followed by a short essay by Zackary Sholem Berger on modern both secular and orthodox Yiddish literature where he sadly observes how few authors are left who can still write in Yiddish. Perhaps, those secular writers, who use their pen to make a living, is about a minyan (ten male Jews required for public prayer): the number of people on staff at the Yiddish Forward. Berger also lists worthwhile contemporary Yiddish publications: Forverts, Gilguim founded in 2008 by Gilles Rozier in Paris, and which is a pure pleasure to read from the first to the last pages. Among the authors, he admires are the ones published by Gilguim, Mikhail Krutikov and his strict, erudite, and tightly edited Forverts’ reviews, Alexander Spiegelblatt with his excellent post-Holocaust prose, and of course Avrom Sutzekever who whose poetry Berger calls a blessing. He argues that the challenges faced by secular Yiddish writers are twofold: first, their readership is inexistent or at least, shrinking dramatically; secondly, they are a minority within the Yiddish minority. Hassidic Yiddish speaking Jews do not read them since they have no incentive to explore secular literature while they have their own books. But the final words of this rather gloomy summary are encouraging because Berger hopes that one of those “strange things [that] occurred to Jews and Yiddish” might happen again, and that future Yiddish classics would write outside the present “two-poles (Hassidic and secular) model of contemporary Yiddish culture”. He looks forward to it. So do we.

From a slightly different perspective, the same issue is visited by Gilles Rozier interviewed by Karolina Szymaniak. Rozier, who started Gilguim mentioned by Berger above in 2008, believes it makes sense to publish a literary review in Yiddish because number wise, the readership of parallel e.g. French publications is the same, about 500 people. Rozier, writer and poet himself, writes both in French and in Yiddish. When pushed by his interviewer with a statement that in Poland, many people believe Yiddish literature is a ground reserved to “a few researchers and lunatics”, he did not hesitate to respond that “those lunatics dedicated to Yiddish are extremely interesting persons”, and added that “when millions go to the theatre to see Avatar, he prefers to read Sutzekever quietly with his friends”.

However, his picture of Yiddish culture is not cheerful at all but also gives hope. In the multicultural European Union supporting different minorities, it might be easier now to cherish and preserve, and even promote the development of, a language spoken by several hundreds of thousands people in the world than it had ever been before. And it might not be a vernacular language of millions of Jews who used to populate Central and Eastern Europe but on the other hand, Yiddish has probably never had as many non-Jewish speakers with academic background. He confesses “I would not be the same man, the same Jew, had I not learned Yiddish” (Yiddish is a language of choice for him). He observes how difficult it is to hold Yiddish summer schools, celebrate Jewish festivals and klezmer workshops in “a dessert that seventy years ago, was the largest ever killing field of Jews”; “all those joyful celebrations take place on the edge of a common grave. After all, it is likely to be our most powerful incentive: perhaps Yiddish will finally let us move away from this edge.”

On the following pages, we find an exquisite homage to an exquisite poet, Avrom Sutzekever. A genuine poetic feast: several short poems from his books: Oasis, Poems from My Dairy, Elephants at Night. What a shame the feast lasts a short twinkle of a star! Let us stop and extend this while:

Gray Fire

Who creates the gray in your hair?

Don’t you know, brother:

Between the earth and sky, a spinning wheel –

On the spinning wheel hangs the gray fire,

Nearby, on a cloud

Sits your own skeleton,

He cherishes your dying,

And spins your hair

The gray fire. [2]

Commemoration to Sutzekever z’’l… It is hard to believe he is no longer with us. Perhaps the last romantic poet-hero of the 20th century; he who seemed indestructible under the shield of his poetic and esthetic finesse, survivor from the Vilna ghetto and rescuer of Yiddish cultural treasures, witness of Jewish national revival and shrinking dominium of his beloved mother tongue, Yiddish to which he had always opposed through his poems. In Yiddish, he sang his song of humanity and the universe; not a religious poet himself, he translated the faith of his forefathers into a story of Jewish and human pilgrimage through the 20th century in a sequence of dichotomies of di groyskayt fun kleynkayt and the extraordinary in the ordinary like e.g. the infinite barbarity of Nazis against the infinite beauty of his Vilna poems composed in perfect rhyme. He believed poetry had magical power to change reality and overcome the death. Sutzkever and Vargas Llosa seem to serve the same case: “Without fictions we would be less aware of the importance of freedom for life to be livable, the hell it turns into when it is trampled underfoot by a tyrant, an ideology, or a religion. […] literature not only submerges us in the dream of beauty and happiness but alerts us to every kind of oppression” [3].

One poem, To Poland (Tsu Poyln), the last published on the commemoration pages, being an opus magnum of this issue, is also very meaningful in the context of what the Cvishn pursue to accomplish through their cultural endeavors. To Poland, as ironic as it may seem, was not known in Poland. This long poem, written in romantic tradition (and subverting it) after the Kielce pogrom of 1946, and making references to great Polish romantic poets, and historical events shared by the two nations, is Sutzkever’s farewell with Poland once he decided to emigrate to “forget about nightmares” though he earlier believed “that a few lone rescuers, / were more than one thousand villains and traitors”. He decided to share the fate of so many eternal Jewish wanderers before him: “So we are going, our souls burning”[4] because the brotherhood of blood shed disappeared after the war letting in the ghosts of enmity and obscurantism. It is a poetic synthesis and recount of centuries long Polish and Jewish neighborhood. Again, we can see how unilateral this relationship between the two neighbors, the Jews and Poland, their “whole sister in the motherland”, was.

The poem is printed in both Polish and Yiddish and its background is made of documents evidencing Sutzkever’s correspondence and bonds of friendship with another poetic giant of their times, Czesław Miłosz who happened to be born in Vilna too, in his case, Polish Vilna. Chone Shmeruk [5] , Jewish literary historian and Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, Polish anthropologist, comments on the poem follow.

Obviously, this summary is to entice readers and cannot include even a brief recount of all the valuable works and articles published on 198 pages of this Cvishn issue. The curious reader will find some guidance in the detailed List of Contents. But I cannot leave out without recommending an authentic linguistic gem: Street and Yard Advertisements (From Warsaw Folklore) by Meylekh Gromb, a collection of sales pitches and catchy phrases used by przekupkies (huckstresses) published in 1929 in the 3rd issue of the Filologishe Shriftin edited by eminent linguists: Max Weinreich and Zalmen Rayzen. Gromb’s article is introduced and commented by a renown Polish linguist, Prof. Ewa Geller.

Closing my notes, I would like to mention two cultural presentations. They all show that modern Yiddish culture is fine and alive, and has interesting messages and visions to communicate. The first is a poetic confession by Prof. Haim Maor about the sources of his torments and inspirations. Then we have a story of the Crystal Clear exhibit held in 2009 in Tel Aviv, in the Kayma Gallery. It gathered seventeen young and mature artists who created their projects especially for this exhibition inspired by the collection of Jewish books kept in the Gallery. “The artists were impressed by the books, language and the concept of time they imply, and also with the complexity of memories and pains they somehow bring along. We felt we were accompanied by the awareness and imaginaries of the Destruction which raised our anxiety. We opted for a modern view on Yiddish culture to be able to cope with the imbroglio of painful memories and avoid turning the exhibit into a place of remembrance and mourning of the dead.” The response to the exposition was huge. “It has proven it is high time to approach Yiddish culture from an artistic angle.”

This issue contains all the above and more: pieces of postwar prose, visits to Yiddish centers in Melbourne and Hamburg, article on the Próżna Project, the only street of the Warsaw Ghetto that escaped annihilation, historical materials on the rescue of Yiddish cultural treasures from the fires of the Vilna Ghetto, and reflections on the events of March 1968 in Poland. There are some reviews, comments and opinions, and information on some recent and future events.

You are warmly invited to visit and enjoy this new magazine devoted to Yiddish and Yiddish culture excellently edited by a group of enthusiasts yet knowledgeable specialists in their craft whose love and tenderness for Yiddish transpires from every page of this publication.

[1] Opening words of one of his poems from Poems from my Dairy.

[2] Abraham Sutzkever, Barbara Harshav, Benjamin Harshav A. Sutzkever: Selected Poetry and Prose, Oxford, England: University of California Press, 1991, p. 268.

[3] Mario Vargas Llosa, Nobel lecture, December 7, 2010.

http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/2010/vargas_llosa-lecture_en.html accessed on December 14, 2010.

[4] Quote after I.L. Peretz, from the drama Di Goldene Keyt (The Golden Chain).

[5] Chone Shmeruk, Avrom Sutzvkever un poylishe poezye: Juliusz Słowacki in der poeme ”Tsu Poyln” in: Yikhes fun lid – lekoved Avrom Sutzkever, Tel Aviv: Yoyvl Komitet, 1983, pp. 280–291.

Dofinansowano ze środków Ministerstwa Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego w ramach

Dofinansowano ze środków Ministerstwa Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego w ramach